Blog post researched and written by Spring 2021 HSHSL Intern, Elizabeth Brown. Elizabeth is a student of the Masters of Library and Information Science program at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. She recently completed an internship at the HSHSL working with the Historical Collections.

The Health Sciences and Human Services Library Historical Collections’ strives to provide broad access to our diverse collections both in person and digitally. Materials in our collections appear as they originally were published or created and may contain offensive or inappropriate language or images and may be offensive to users. The University of Maryland, Baltimore does not endorse the views expressed in these materials. Materials should be viewed in the context in which they were created.

The case of the missing apparatus:

On March 29, 1822 a minor but interesting scandal was recorded. From the University of Maryland Faculty Minutes 1812 – 1839[1] (page 14):

“D Hoffman Esq & Drs Pattison & Howard to attend were appointed a committee with instructions to make an arrangement with the representative of Monsieur Mercier of the firm late of this city ‘Decaves & Mercier’ relative to a debt of Five thousand Dollars due by him to the University of Maryland. This being the amount of a bill of exchange entrusted to him for the purchase of Chemical & Philosophical apparatus in Paris [crossed out] whether he was then going. and [sic] of the amount of which he defrauded the University.”

To wit: the University entrusted $5000 (the equivalent of $113,195 today[2]) to a French company in order to buy scientific, laboratory equipment in Paris but the person who they trusted to make the purchase took the money and ran. The faculty formed a committee to try to recover what they were owed, although the results of their efforts isn’t recorded.

But what were “Chemical & Philosophical apparatus” at that time?

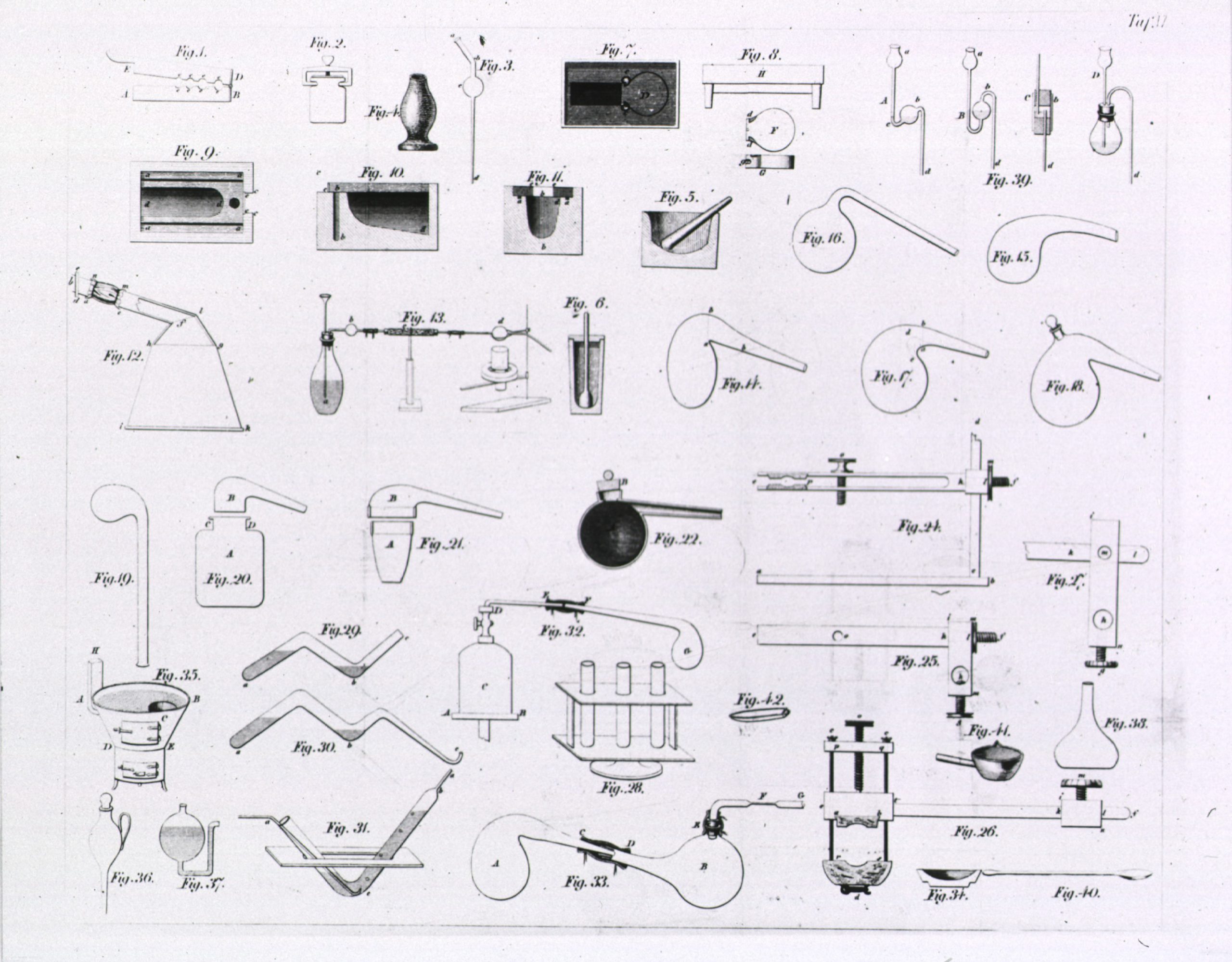

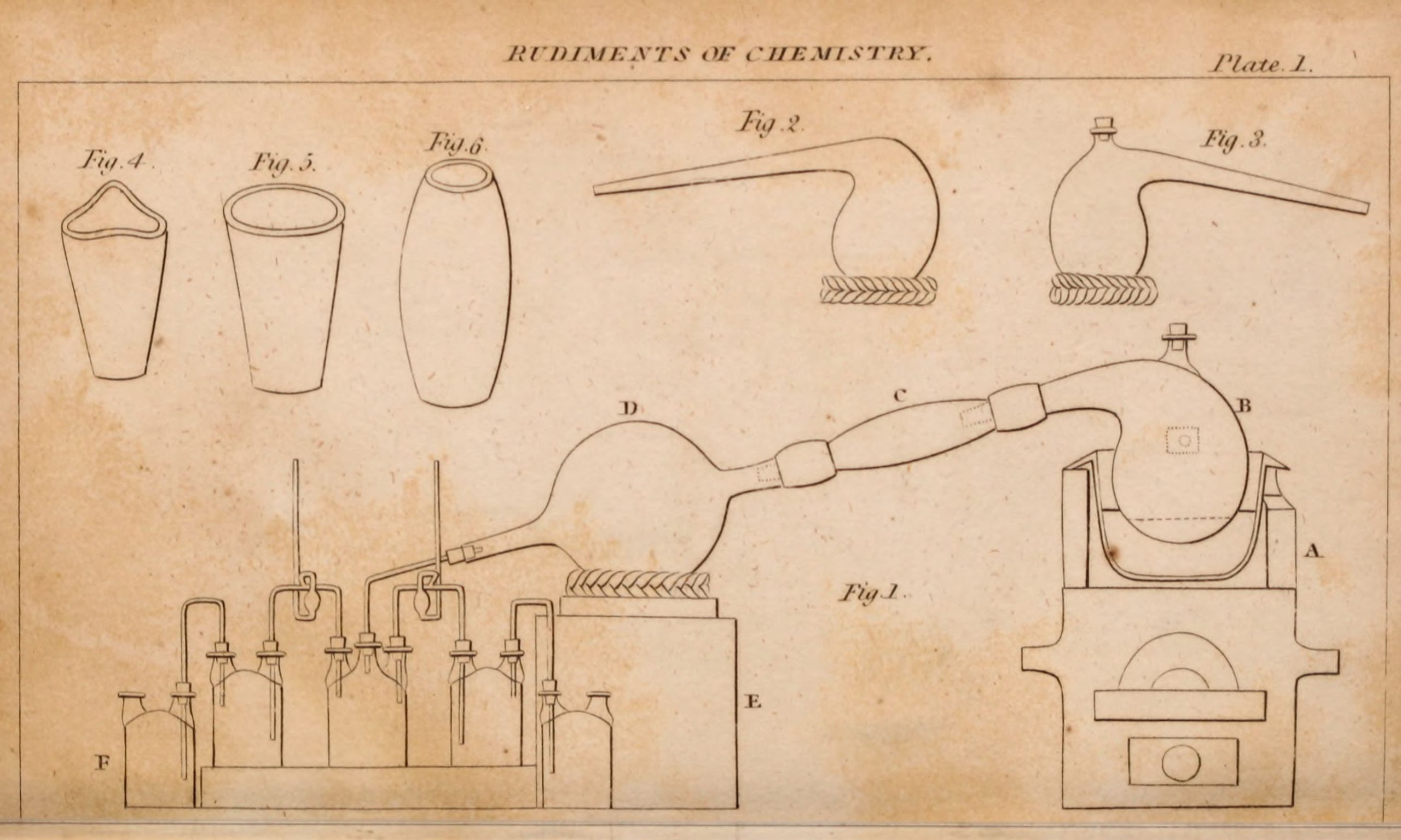

Contemporaneous examples of the chemical equipment are illustrated in The Rudiments of Chemistry by Samuel Parkes (1823)[3] along with instructions on the equipment’s use for demonstrating chemical theorems and how they could be applied on matter as it was understood at the time. These include glassware that was frequently created for distilling purposes such as retorts, bladders, and funnels.

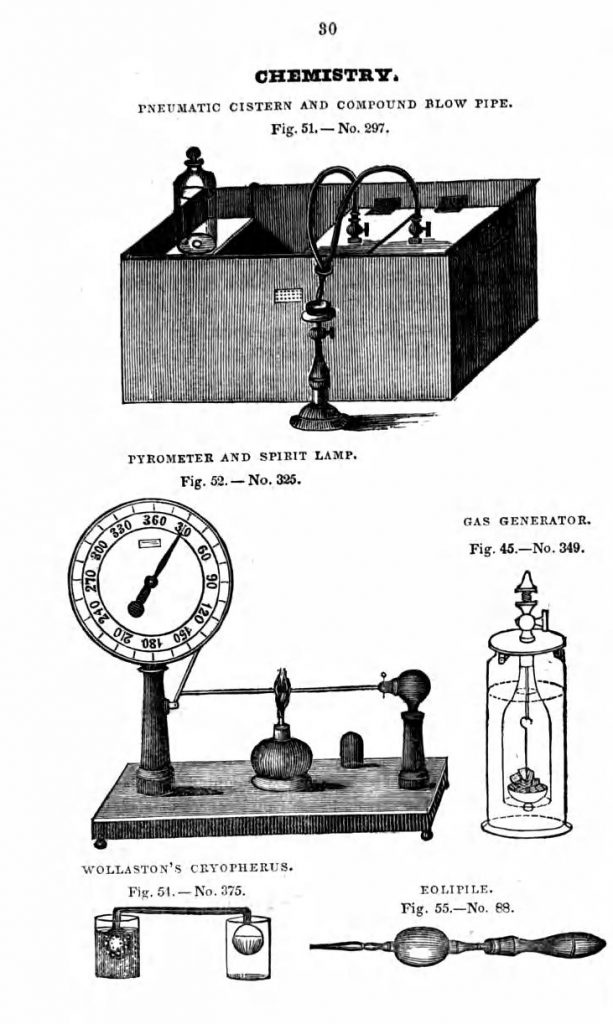

“Philosophical apparatus” referred to scientific equipment used for conducting experiments in other, often newly-developing, fields of science such as astronomy and electricity. Examples can be seen in Catalogue of the philosophical apparatus, minerals, geological specimens &c by Charles Daubeny (1861)[4] and in A catalogue of philosophical, astronomical, chemical and electrical apparatus by Joseph M Wightman (1846) [5].

Numerous purchases of “apparatus” are recorded in Eugene Cordell’s histories of the University of Maryland[6] including an initial sum of $50,000 ($752,941 in today’s currency[7]) endowed for the purpose of buying “chemical and scientific apparatus and anatomical preparations” (Cordell 31) when the University was established by Acts of the state legislature 1814. This collection grew incrementally over time, with different faculty purchasing equipment to use for demonstration purposes in their lectures and occasionally donating their personal collections to the University. Eventually enough materials were amassed that the collections became distinguished as “Chemical apparatus” budgeted for $8300 ($238,965 modern currency[8]) in 1830 (Cordell 68).

Numerous purchases of “apparatus” are recorded in Eugene Cordell’s histories of the University of Maryland[6] including an initial sum of $50,000 ($752,941 in today’s currency[7]) endowed for the purpose of buying “chemical and scientific apparatus and anatomical preparations” (Cordell 31) when the University was established by Acts of the state legislature 1814. This collection grew incrementally over time, with different faculty purchasing equipment to use for demonstration purposes in their lectures and occasionally donating their personal collections to the University. Eventually enough materials were amassed that the collections became distinguished as “Chemical apparatus” budgeted for $8300 ($238,965 modern currency[8]) in 1830 (Cordell 68).

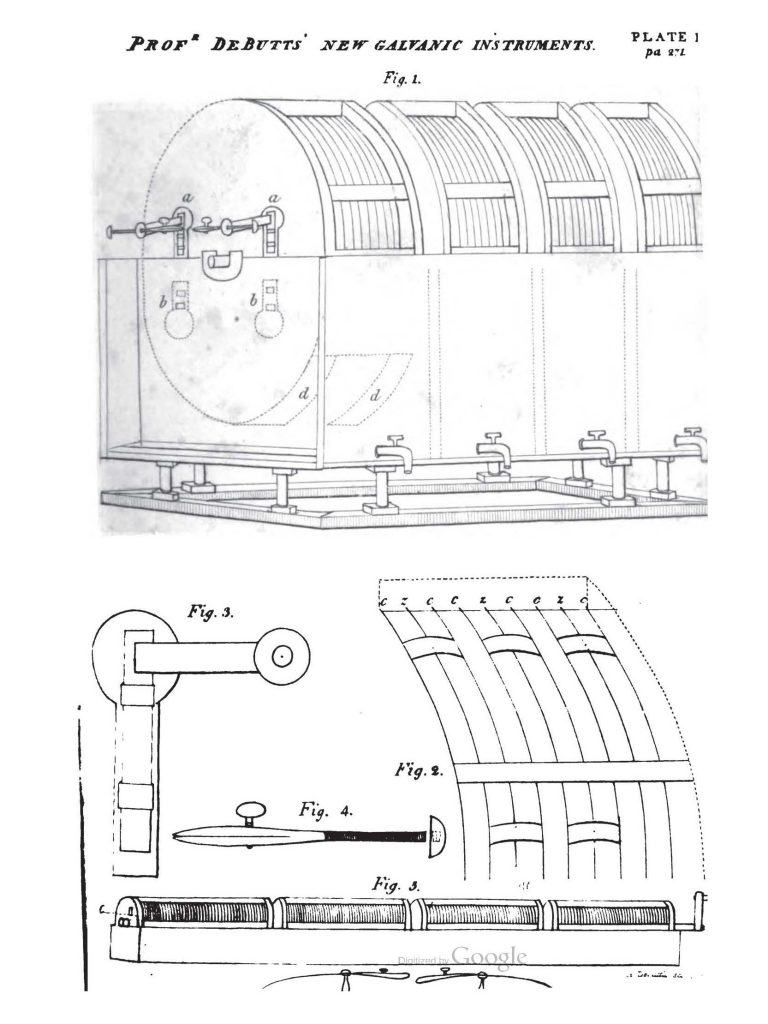

Cordell mentions how an “immense galvanic apparatus” (Cordell 189) created by Chemistry Professor Elisa DeButts[9] was brought out for demonstration when General Lafayette, the French aristocrat and acclaimed military officer in the American Revolutionary War, paid a ceremonial visit to the University in 1824.

An 1838 course catalog for the School of Medicine boasts[10]:

“The Chemical and Philosophical apparatus of this University is of great extent and value, much of it having been selected in Europe by the late distinguished Professor Debutts. And to a Laboratory, provided with every thing necessary for a course of Chemical Instruction, are united the numerous and varied articles required to illustrate the lectures on Pharmacy and Materia Medica. Neither expense nor care has been spared to secure for the University of Maryland, the facilities necessary for the acquisition of thorough Medical Education.”

The school also purchased equipment to remain up to date on new technologies and to provide more advanced levels of classes for its students as the school grew in size, stature, and scope. Joseph Roby, the chair of Anatomy between 1842 and 1860, is cited as the earliest teacher to incorporate the use of microscopes into his lectures. (Cordell 230) Classes which trained students on using microscopes eventually became a required part of the syllabus in 1895. (Cordell 432) The value of experiential learning is described in the 1844-1845 course catalog describing Professor William E A Aikin’s course on Chemistry and Pharmacy: “The apparatus in this department is believed to be unequalled by that of any other Institution, an affords every possible facility for teaching a science which can only be taught by experiment.”[11]

The school also purchased equipment to remain up to date on new technologies and to provide more advanced levels of classes for its students as the school grew in size, stature, and scope. Joseph Roby, the chair of Anatomy between 1842 and 1860, is cited as the earliest teacher to incorporate the use of microscopes into his lectures. (Cordell 230) Classes which trained students on using microscopes eventually became a required part of the syllabus in 1895. (Cordell 432) The value of experiential learning is described in the 1844-1845 course catalog describing Professor William E A Aikin’s course on Chemistry and Pharmacy: “The apparatus in this department is believed to be unequalled by that of any other Institution, an affords every possible facility for teaching a science which can only be taught by experiment.”[11]

But the equipment wasn’t considered valuable just for its educational uses. Cordell recounts several instances of equipment being stolen, including this instance in 1837:

“They [University faculty and staff] found some articles missing from the Museum which had been claimed by members of the Regents’ Faculty as private property. They also found in one of the rooms of his house three vessels that had contained liquors, and a coarse bowie-knife made out of part of an old sword, which one of the young men afterwards called for…” (Cordell 81)

“They [University faculty and staff] found some articles missing from the Museum which had been claimed by members of the Regents’ Faculty as private property. They also found in one of the rooms of his house three vessels that had contained liquors, and a coarse bowie-knife made out of part of an old sword, which one of the young men afterwards called for…” (Cordell 81)

While the specialized glassware remained rare, it was kept locked up in the classrooms and laboratories as much as possible to prevent such cases of theft and misuse. With time, the materials that were being purchased would eventually become easier to make and acquire, allowing for less restrained access. The same year microscopy became a required part of the syllabus, Cordell notes: “The Chemical Laboratory previously open chiefly for class instruction, was so arranged as to give students an opportunity for individual work at any hour of the day, under the guidance of Professor Daniel Base…” (Cordell 432)

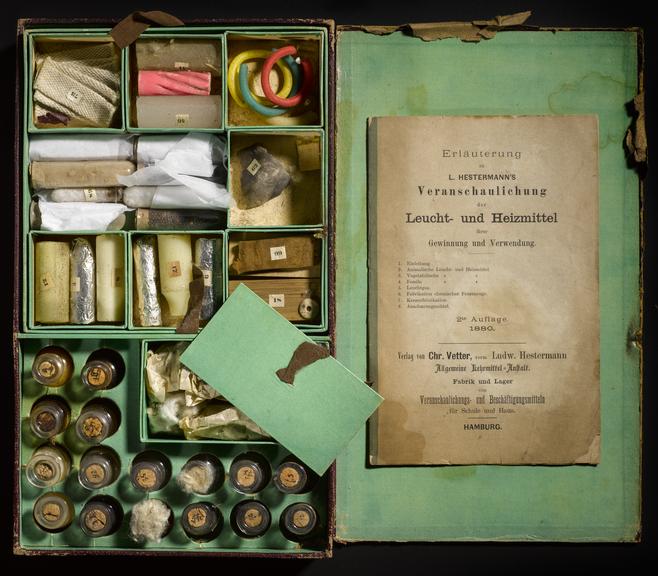

Eventually the materials become so accessible that they were transformed from “chemical apparatus” to “chemistry sets”- an educational toy sold to children.[12] [13] [14]

Footnotes:

Footnotes:

[1] University of Maryland Faculty Meeting Minutes 1812 – 1839. Available at: https://archive.hshsl.umaryland.edu/handle/10713/6322

[2] CPI Inflation Calculator. Available at: https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1822?amount=5000

[3] Parkes, Samuel. (1823) The rudiments of chemistry; illustrated by experiments and copper-plate engravings of chemical apparatus. Available at: https://archive.hshsl.umaryland.edu/handle/10713/3080

[4] Daubeny, Charles. (1861). Catalogue of the philosophical apparatus, minerals, geological specimens, & c. in the possession of Dr. Daubeny, Praelector of natural philosophy in Magdalen college, and now deposited in the building contiguous to the Botanic gardens, belonging to that society. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/28100

[5] Wightman, Joseph M. (1846) A catalogue of philosophical, astronomical, chemical and electrical apparatus. Available at: https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/cataloguephilos00wigh

[6] Cordell, Eugene F. (1907) University of Maryland, 1807-1907, its history, influence, equipment and characteristics, with biographical sketches and portraits of its founders, benefactors, regents, faculty and alumni. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10713/12583

[7] CPI Inflation Calculator. Available at: https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1814?amount=50000

[8] CPI Inflation Calculator. Available at: https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1830?amount=8300

[9]“Mechanics, Physics, Chemistry, and the Arts.” (1824) The American Journal of Science and Arts. Available at: https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_American_Journal_of_Science_and_Arts/ZEBSAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=galvanic+apparatus+elisha+debutts&pg=PA271&printsec=frontcover

[10] University of Maryland, School of Medicine Catalog 1838-1880. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10713/2619

[11] University of Maryland, School of Medicine Catalog 1838-1880. Available at: https://archive.org/details/medicine37unse/page/n82/mode/1up?q=Apparatus

[12] Cook, Rosie. (April 6, 2010) “Chemistry at Play.” Science History Institute. Available at: https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/chemistry-at-play

[13] Zielinski, Sarah. (October 10, 2012) “The Rise and Fall and Rise of the Chemistry Set.” Smithsonian Magazine. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-rise-and-fall-and-rise-of-the-chemistry-set-70359831/

[14] “Playing with Science: A Brief History of the Chemistry Set.” (May 15, 2019). Science Museum. Available at: https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/chemistry/playing-science-brief-history-chemistry-set