The Health Sciences and Human Services Library Historical Collections’ strives to provide broad access to our diverse collections both in person and digitally. Materials in our collections appear as they originally were published or created and may contain offensive or inappropriate language or images and may be offensive to users. The University of Maryland, Baltimore does not endorse the views expressed in these materials. Materials should be viewed in the context within they were created.

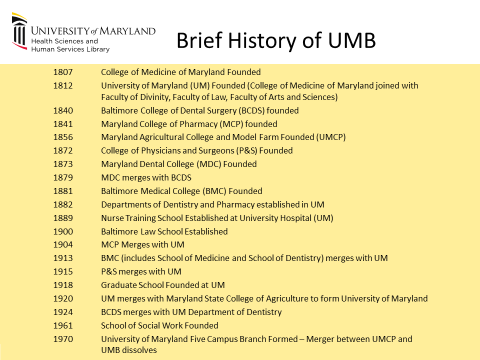

Brief Timeline of the history of UMB, curated by Tara Wink, Historical Collections Librarian and Archivist.

March is Women’s History Month, the HSHSL will celebrate the month by honoring select UMB women through our blog and an exhibit, The First Women of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, in the Weise Gallery. The University of Maryland, Baltimore as it is known today was formed through a number of mergers with other Baltimore area Colleges and Universities; additionally, the school was once a branch campus of the University of Maryland, College Park. Because of this, the history of women at UMB is intermingled with the histories of these schools and each accepted women into their programs at different times.

Dr. Emilie Foeking, Baltimore College of Dental Surgery, Class of 1873. The first woman to graduate from a medical or dental school in Baltimore.

The first woman graduate from any Baltimore medical or dental school was Emilie Foeking. She graduated in March 1873 from the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery (BCDS), which merged with the School of Dentistry in 1924. Dr. Foeking received admission to the BCDS through an appeal to the dean, Dr. Ferdinand Gorgas, after being rejected from the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery. Dr. Foeking’s thesis, “Is Woman Adapted to the Dental Profession?,” was published in the American Journal of Dental Science in April 1873 and argued that women were in fact well suited for the dental profession. The press had its own opinions. A very short mention of Dr. Foeking’s performance is given in the graduation announcement; instead the papers reported on what she wore and how she looked: “…according to the professors, also passed the examination in a highly satisfactory manner… The graduation of a young lady in dentistry is such a novelty in this country that the appearance of Miss Foeking created a ripple of surprise. She was attired in the height of fashion and very handsomely, having a white silk dress with pink overskirt. When she stepped up to receive her diploma she was greeted by a thunder of applause from the spectators, and was the recipient of numerous bouquets and a handsome case of wax flowers.”[i] Her graduation was treated as show instead of the incredible accomplishment it was for women in Dentistry. Following Dr. Foeking’s success, the BCDS continued to accept and graduate women; the following year Louis Jacobi became the second woman to graduate from the school. Both women returned to Europe to practice dentistry, where women dentists were more common according to Dr. Else Roof, University of Maryland School of Dentistry, Class of 1915.[ii]

Louisa Parsons, first Superintendent of the University Hospital Training School for Nurses, the precursor of the School of Nursing.

In 1889, the University of Maryland Hospital was in the process of opening a Training School for Nurses. Louisa Parsons, a nurse trained in the Nightingale Fund Training School for Nurses at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London, was hired as its first superintendent. Parsons became the first woman to hold such a prestigious position within the hospital and medical school. She oversaw the two-year curriculum of the precursor to UMB’s School of Nursing for two years; stepping down in 1892, she set the school on a solid foundation for future success.

First graduating class of the University Hospital Training School for Nurses, 1892.

In 1892 the Hospital Training School of Nurses graduated eight women: E. Dunham, L. Dunham, M. Goldsborough, J. Hale, A.E. Lee, K.C. Lucas, A. Neal, and A.L.K. Schleunes. Enrollment grew substantially in the following years, reaching 55 students—again all women—in 1905. In fact, the first time a man graduated from the School of Nursing was in 1961 when Hector J. Cardellino received his degree. This is the only school where men have consistently been the minority at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

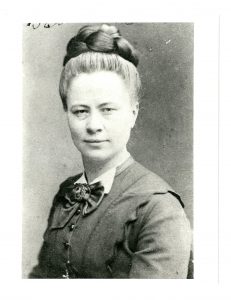

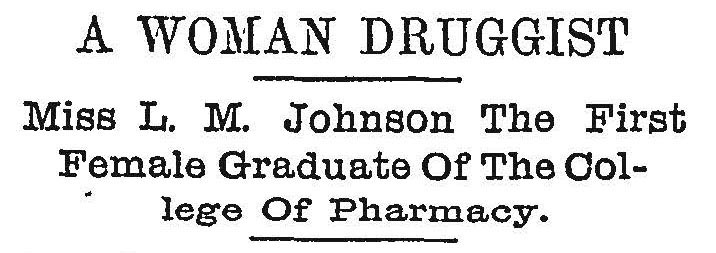

In 1898, Lady Mary Johnson became the first woman graduate of the Maryland College of Pharmacy (MCP), which merged with the School of Pharmacy in 1904. Dr. Johnson had already received her medical degree from the Women’s Medical College of Baltimore in 1897 before enrolling in the MCP. The Women’s Medical College, was formed in 1882 in an effort to provide women with an adequate medical education as more and more schools in the state shuttered their doors to women. The school graduated 116 women before closing its doors in 1910.

The Baltimore Sun’s Newspaper Announcement of Dr. L.M. Johnson’s Graduation from the Maryland College of Pharmacy in 1898.

Unlike the article announcing Dr. Foeking’s graduation the newspapers presented the stirring words of Reverend Dr. H.M. Wharton, who challenged the men in the class to push harder, lest they fall behind women. “Had I known that I should have been selected to appear as an orator on this occasion, I should have been as hard to find as the Spanish fleet, for whom our navy is now looking. This is the first time in the history of this school that a woman has been honored with a diploma. In times past woman has been relegated to the rear; indeed, it has been thought that her duties were confined to household work, even to handling the kettles and pans, but now woman has come forward and has begun the battle of the ‘survival of the fittest.’ She has not acquired this position by her winning ways or her pretty face, but has won her position by her intellect. I congratulate the Maryland College of Pharmacy for having opened their doors to women. To you young men of this class I would say, be careful that you are not relegated to the rear.”[iii] Rev. Dr. Wharton appears to have a higher opinion of women in professional positions, perhaps this is due to Dr. Johnson’s physician degree received prior to her pharmacy degree. More likely it is the signs of progress for women that the turn of the century would bring.

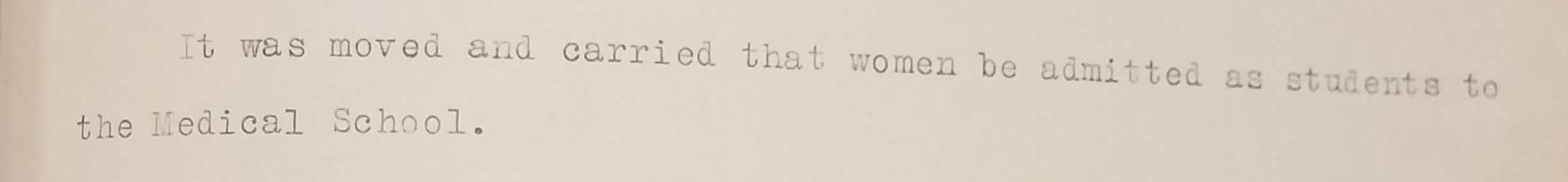

Line from the January 8, 1918, Faculty of Physik Meeting allowing women to apply to the School of Medicine.

Twenty years after Dr. Johnson’s graduation, women would finally be allowed to join the School of Medicine, when the Faculty of the School voted to accept women. The faculty were reacting to a significant drop in enrollment and an increased demand for doctors due to the United States involvement in World War I and mounting pressures for a public university, which received funds from the state, to accept women. By 1923, two women were members of the senior medical class.

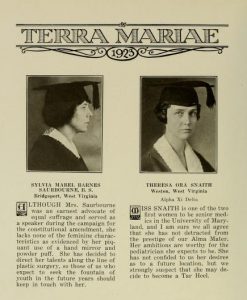

1923 Terra Mariae Yearbook, photographs of Dr. Theresa O. Snaith, Class of 1923 and Dr. Sylvia M.B. Saurborne, Class of 1924.

Dr. Theresa Ora Snaith, became the first woman to graduate from the school that year; her classmate, Dr. Sylvia Mabel Barnes Saurborne, would graduate the following year (1924). Both women were pictured in the Terra Mariea Yearbook for 1923. Dr. Snaith’s superlatives suggest the general reception she must have received from her male counterparts: “…I am sure we all agree that she has not detracted from the prestige of our Alma Mater.” Dr. Barnes’s superlatives are even harsher: “Although [she] was an earnest advocate of equal suffrage and served as a speaker during the campaign for the constitutional amendment, she lacks none of the feminine characteristics as evidenced by her piquant use of a hand mirror and powder puff.” Neither doctor received recognition for her medical abilities nor for her strengths for blazing a trail for future women physicians; they merely did not detract from the education of their male colleagues. Women in the School of Medicine for years after the first graduates would speak of obstacles in admittance from faculty as well as inappropriate comments from classmates who believed that “Medical school is no place for a woman.”[iv]

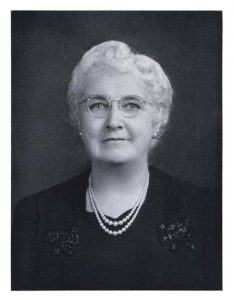

Dr. B. Olive Cole, “First Lady of Maryland Pharmacy”, School of Pharmacy Class of 1913, School of Law Class of 1923, Dean of the School of Pharmacy 1948-1953

Commencement exercises in 1923 also saw the first women graduates in the School of Law: B. Olive Cole (also a graduate of the School of Pharmacy in 1913), Fannie Kurland, Ida Clare Lutzky, Marie Presstman, and Helen I. Sherry. The School of Law first accepted women in 1920. Prior to that women were rejected because “there were no restrooms for women.[v]” In 1920, there were still no restrooms for women, they had to use those across the street at the School of Medicine. However, Dr. A. F. Woods, president of the University of Maryland, had the following promising words to say about the women graduates of 1923 and those 100 others still enrolled in the school (at this time the University of Maryland was one school with campuses at College Park and Baltimore): “They are better students than men. They study harder, behave themselves and as an average grade higher then the men. This institution holds every welcome for them and believes that they will come along in greater numbers in future years.”[vi] Women had made their mark at the University of Maryland and signs were pointing to their future successes in new professions and in leadership roles within the school.

These early women graduates faced obstacles and had their detractors, yet they were trailblazers and leaders for today’s women. They faced critics who saw no reason to educate women in the professional fields, as they would surely leave their positions after marriage and children. They faced rejections of positions in favor of men and questions wondering about their career choices. Yet they succeeded. This month celebrates these early women and those that have followed to make the University of Maryland, Baltimore stronger.

References:

“A Woman Druggist…” (20 May 1898) The Sun (1837-1993); ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Sun:7.

“Asserts women lead at U. of M….” (11 Jun 1923). The Sun (1837-1994); ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Sun: 3.

“Commencement of the College of Dental Surgery—A Young Lady Among the Graduates.” (1 March 1873) The daily dispatch. (Richmond [Va.]). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. Retrieved from: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024738/1873-03-01/ed-1/seq-3/.

Hyson, J.M. (June 2002). “Women Dentists: The Origins.” Journal of the California Dental Association. 30(6):444-451. Retrieved from: https://www.cda.org/Portals/0/journal/journal_062002.pdf.

Innovation in Action: The University of Maryland School of Nursing from its Founding in 1889 to 2012. (2014). Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/10713/7106.

Jablow, M. and J. Walker. (1972). Bulletin of the University of Maryland School of Medicine. 57(3): 1-9. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/bulletinofuniver5757/page/n71/mode/2up.

“Local Matters.” (28 Feb. 1873). The Sun (1837-1993); ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Sun: 1.

McCausland, C. (2018). “Empowered to Practice: Maryland Celebrates 100 Years of Admitting Women.” Bulletin of the University of Maryland School of Medicine. 10(2): 6-13. Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/10713/8290.

“New Dentists.” (28 Feb. 1874). The daily dispatch. (Richmond [Va.]), 28 Feb. 1874. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. Retrieved from https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024738/1874-02-28/ed-1/seq-3/.

Romer, L. (2009). “Raising a Gavel for Women’s Equality.” University of Maryland: Research & Scholarship. 18-20. Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/10713/93.

“She Likes Dental Work…” (28 Nov. 1912). The Sun (1837-1993); ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Sun:4.

Terra Mariae. (1923). University of Maryland, Baltimore. Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/10713/2479.

End Notes:

“I Belong Here” – Dr. Bella F. Schimmel, School of Medicine Class of 1952. From McCausland, C. (2018). “Empowered to Practice: Maryland Celebrates 100 Years of Admitting Women.” Bulletin of the University of Maryland School of Medicine. 10(2): 6-13.

[i] “Commencement of the College of Dental Surgery—A Young Lady Among the Graduates.” (1 March 1873) Richmond Dispatch.

[ii] “She Likes Dental Work…” (28 Nov. 1912). The Sun (1837-1993); ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Sun:4.

[iii] “A Woman Druggist…” (20 May 1898) The Sun (1837-1993); ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Sun:7.

[iv] Dr. Martha E. Stauffer, School of Medicine Class of 1960. From McCausland, C. (2018).

[v] Romer, L. (2009). “Raising a Gavel for Women’s Equality.” University of Maryland: Research & Scholarship.

[vi] “Asserts women lead at U. of M….” (11 Jun 1923). The Sun (1837-1994); ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Baltimore Sun: 3.