It’s possible to read this quote and think it was written about Baltimore today, yet it describes Baltimore 102 years ago, when the city and University were in the throes of another deadly pandemic. The world 102 years ago was drastically different than today’s world. 1918 marked the final year of World War I – a deadly four-year conflict believed at the time to be “the war to end all wars.” The war spurred advances in both military and civilian technology and mobility – advances that facilitated the spread of a particularly virulent flu across the globe.

The 1918 flu was known as the Spanish Flu because Spain, having maintained neutrality during World War I, was the only nation reporting cases of the illness. As a result, Spain was wrongfully assumed to be the starting point for the flu. In 1918, people, mostly troops, were more easily moving all over the world through railroads, planes, ships, and submarines. People were also communicating in relatively new ways: via radio and telephone. The circumstances surrounding the war created a world more connected than ever before, yet a world weakened by wartime production, destruction, and strain. A perfect storm for the 1918 influenza virus.

Today, like 1918, the world is also experiencing unprecedented technological advances. Today we are not in the throes of a world war, yet the world is interconnected like never before. People travel the world with relative ease and speed through the availability of passenger airline flights and cruise ships. We can also communicate in ways never imagined in 1918. Today, instead of fighting a visible enemy in a world war, we fight an invisible one: COVID-19. This pandemic, like the “Spanish Flu”, has affected every part of the world and bears eerie similarities to the 1918 pandemic.

The 1918 flu hit in three phases: the first hit the United States in March 1918, the second and deadliest hit in September 1918, and the third in December 1918. Like COVID-19 today, the second phase shut down entire cities, including Baltimore. When the flu arrived in Baltimore in September 1918, the initial response, in an effort to support the war effort and maintain morale, was to continue business as usual. People believed the virus was no different than those experienced in the past, but as more and more people fell victim, the city health commissioner, Dr. John Blake, enacted more and more restrictions, shutting down businesses, schools, and places of worship for roughly a three-week time period.

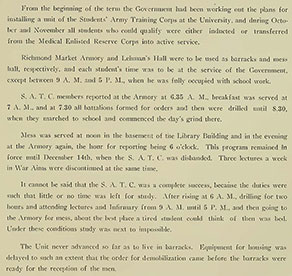

The University of Maryland, Baltimore was not immune to these restrictions. In 1918 the University of Maryland included the Schools of Medicine, Dentistry, Pharmacy, and Law, as well as the Nursing Training School—which was under the guidance of the University Hospital—and the College of Arts and Sciences located at St. John’s College in Annapolis. The fall semester began with placement testing for students in Medicine, Dentistry, and Pharmacy in late September 1918, and classes began October 1, 1918, roughly the same time that the flu was introduced into Baltimore City. At the beginning of the fall term, male students were inducted into the Student Army Training Corps (S.A.T.C.) a program that allowed the students to continue to learn their professions while also training as soldiers to join the war effort. Across the schools, students seemed to have the same opinion of the S.A.T.C., finding it an unwelcome interruption to their studies. The class histories in the yearbooks regularly comment on the terrible food in the “mess hall,” claiming it “jeopardize[d] their stomachs with such things, as diseased macaroni, stewed potatoes in a pathological condition, etc.” The 1919 Senior Class Dental History provides an excellent overview of the student’s new schedules. All class histories welcome the end of the S.A.T.C. when the war ended in November 1918.

By October 9, 1918, all coursework and training across the University was stopped by order of Dr. John Blake. At the University, students in the nursing program and in the School of Medicine were called upon to assist in the hospitals connected to the University—University Hospital, Mercy Hospital, and Maryland General Hospital—and private practices around the city as cases of the flu grew and greater numbers of doctors and nurses succumbed to the virus. Newspaper articles from that time reported that the hospitals were often overflowing with patients and forced to turn the sick away.

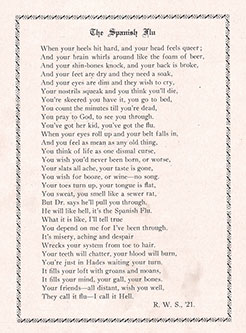

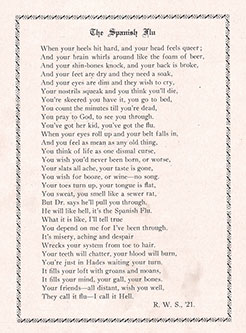

“The Spanish Flu” by Richard W. Schafer, Baltimore College of Dental Surgery Class of 1921, from the 1919 Mirror Yearbook.

When the school reopened in early November 1918, at least ten students and faculty had succumbed to the flu. Others were severely affected by the flu or confined to hospital beds for several weeks or months. Dr. Richard W. Schafer, historian of the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery (merged with the University of Maryland in 1924) Class of 1921, drew on his experience as a flu victim to pen a humorous poem for the 1919 Mirror Yearbook. John W. Felton, historian of the School of Pharmacy Class of 1919, eloquently remembered the flu and its effect on his class and school as follows:

The next great drawback to work was the Spanish Influenza epidemic, which invaded this country early in the Fall, taking a large number of lives, and causing great sadness and sorrow. It was feared and dreaded by all, as it was no respector of rank, and many of the most influential and useful citizens as well as our best-loved friends were taken away. It became so bad and spread so rapidly that the schools, churches, theatres and public gatherings and amusements were ordered closed until the worst of it had passed. As a result of this the University of Maryland was closed for three weeks, thus setting us further back in our work. Many of our classmates contracted the disease, and one of our beloved members, Manuel J. Sans, of Cuba, and also Dr. Miller, who was to be our Quiz Master in Pharmacy and Chemistry, fell victims to the disease and died shortly after taken ill. The deepest sympathy went out among the students in the loss of our beloved classmate and eminent Professor.

Still other students remembered the flu as nothing more than a handicap to their studies, an unwelcome nuisance that cut short their winter break, or an “enforced vacation”.

Generally speaking, the history of the 1918 flu pandemic at the University of Maryland, Baltimore is a short one. The school only closed during the fall, and there is no mention of additional closings during the third phase. The Bulletin of the School of Medicine, the main publication of the school at the time, covers the flu in only one article, while several articles, letters, and notations address World War I. It appears the War and the S.A.T.C. presence on campus had a much larger impact on the school than the flu. The school’s coverage of the flu mirrors press coverage of the 1918 flu, as well. In general, the press covered the war far more thoroughly than it did the flu, even though the flu, having killed 675,000 people, was far more dangerous and deadly than the war, which killed 116,516.

The COVID-19 pandemic has once again shut down many businesses, schools, houses of worship, and other gathering places in Baltimore City. Once again, the University of Maryland, Baltimore is not immune to this pandemic. Today many of our students, faculty, and staff find themselves off campus in the midst of a semester. The 2020 class histories, if written today, would reflect frustrations similar to those of 1918 of a disruption in coursework and scheduling, as well as an unprecedented disappointment as traditional commencement celebrations and events are cancelled. Yet unlike students, faculty, and staff in 1918, we have access to twenty-first century technology that allows us to continue learning, working, and researching. Once again UMB students, faculty, and staff are finding ways to fight an invisible enemy while helping one another and our community.